Luke Zaphir ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

University of Queensland apporte un financement en tant que membre adhérent de The Conversation AU.

Voir les partenaires de The Conversation France

This essay is part of a series of articles on the future of education.

For much of human history, education has served an important purpose, ensuring we have the tools to survive. People need jobs to eat and to have jobs, they need to learn how to work.

Education has been an essential part of every society. But our world is changing and we’re being forced to change with it. So what is the point of education today?

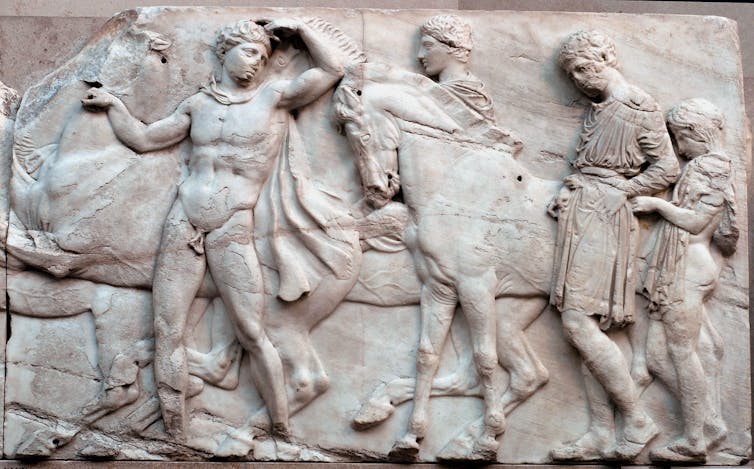

Some of our oldest accounts of education come from Ancient Greece. In many ways the Greeks modelled a form of education that would endure for thousands of years. It was an incredibly focused system designed for developing statesmen, soldiers and well-informed citizens.

Most boys would have gone to a learning environment similar to a school, although this would have been a place to learn basic literacy until adolescence. At this point, a child would embark on one of two career paths: apprentice or “citizen”.

On the apprentice path, the child would be put under the informal wing of an adult who would teach them a craft. This might be farming, potting or smithing – any career that required training or physical labour.

The path of the full citizen was one of intellectual development. Boys on the path to more academic careers would have private tutors who would foster their knowledge of arts and sciences, as well as develop their thinking skills.

The private tutor-student model of learning would endure for many hundreds of years after this. All male children were expected to go to state-sponsored places called gymnasiums (“school for naked exercise”) with those on a military-citizen career path training in martial arts.

Those on vocational pathways would be strongly encouraged to exercise too, but their training would be simply for good health.

Until this point, there had been little in the way of education for women, the poor and slaves. Women made up half of the population, the poor made up 90% of citizens, and slaves outnumbered citizens 10 or 20 times over.

These marginalised groups would have undergone some education but likely only physical – strong bodies were important for childbearing and manual labour. So, we can safely say education in civilisations like Ancient Greece or Rome was only for rich men.

While we’ve taken a lot from this model, and evolved along the way, we live in a peaceful time compared to the Greeks. So what is it that we want from education today?

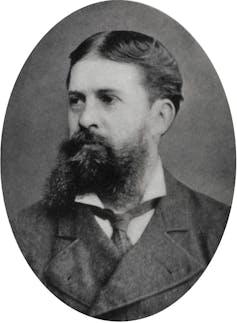

Today we largely view education as being there to give us knowledge of our place in the world, and the skills to work in it. This view is underpinned by a specific philosophical framework known as pragmatism. Philosopher Charles Peirce – sometimes known as the “father of pragmatism” – developed this theory in the late 1800s.

There has been a long history of philosophies of knowledge and understanding (also known as epistemology). Many early philosophies were based on the idea of an objective, universal truth. For example, the ancient Greeks believed the world was made of only five elements: earth, water, fire, air and aether.

Peirce, on the other hand, was concerned with understanding the world as a dynamic place. He viewed all knowledge as fallible. He argued we should reject any ideas about an inherent humanity or metaphysical reality.

Pragmatism sees any concept – belief, science, language, people – as mere components in a set of real-world problems.

In other words, we should believe only what helps us learn about the world and require reasonable justification for our actions. A person might think a ceremony is sacred or has spiritual significance, but the pragmatist would ask: “What effects does this have on the world?”

Education has always served a pragmatic purpose. It is a tool to be used to bring about a specific outcome (or set of outcomes). For the most part, this purpose is economic.

Why go to school? So you can get a job.

Education benefits you personally because you get to have a job, and it benefits society because you contribute to the overall productivity of the country, as well as paying taxes.

But for the economics-based pragmatist, not everyone needs to have the same access to educational opportunities. Societies generally need more farmers than lawyers, or more labourers than politicians, so it’s not important everyone goes to university.

You can, of course, have a pragmatic purpose in solving injustice or creating equality or protecting the environment – but most of these are of secondary importance to making sure we have a strong workforce.

Pragmatism, as a concept, isn’t too difficult to understand, but thinking pragmatically can be tricky. It’s challenging to imagine external perspectives, particularly on problems we deal with ourselves.

How to problem-solve (especially when we are part of the problem) is the purpose of a variant of pragmatism called instrumentalism.

In the early part of the 20th century, John Dewey (a pragmatist philosopher) created a new educational framework. Dewey didn’t believe education was to serve an economic goal. Instead, Dewey argued education should serve an intrinsic purpose: education was a good in itself and children became fully developed as people because of it.

Much of the philosophy of the preceding century – as in the works of Kant, Hegel and Mill – was focused on the duties a person had to themselves and their society. The onus of learning, and fulfilling a citizen’s moral and legal obligations, was on the citizens themselves.

But in his most famous work, Democracy and Education, Dewey argued our development and citizenship depended on our social environment. This meant a society was responsible for fostering the mental attitudes it wished to see in its citizens.

Dewey’s view was that learning doesn’t just occur with textbooks and timetables. He believed learning happens through interactions with parents, teachers and peers. Learning happens when we talk about movies and discuss our ideas, or when we feel bad for succumbing to peer pressure and reflect on our moral failure.

Learning would still help people get jobs, but this was an incidental outcome in the development of a child’s personhood. So the pragmatic outcome of schools would be to fully develop citizens.

Today’s educational environment is somewhat mixed. One of the two goals of the 2008 Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians is that:

All young Australians become successful learners, confident and creative individuals, and active and informed citizens.

By lifting outcomes, the government helps to secure Australia’s economic and social prosperity.

A charitable reading of this is that we still have the economic goal as the pragmatic outcome, but we also want our children to have engaging and meaningful careers. We don’t just want them to work for money but to enjoy what they do. We want them to be fulfilled.

And this means the educational philosophy of Dewey is becoming more important for contemporary society.

Part of being pragmatic is recognising facts and changes in circumstance. Generally, these facts indicate we should change the way we do things.

On a personal scale, that might be recognising we have poor nutrition and may have to change our diet. On a wider scale, it might require us to recognise our conception of the world is incorrect, that the Earth is round instead of flat.

When this change occurs on a huge scale, it’s called a paradigm shift.

Our world may not be as clean-cut as we previously thought. We may choose to be vegetarian to lessen our impact on the environment. But this means we buy quinoa sourced from countries where people can no longer afford to buy a staple, because it’s become a “superfood” in Western kitchens.

If you’re a fan of the show The Good Place, you may remember how this is the exact reason the points system in the afterlife is broken – because life is too complicated for any person to have the perfect score of being good.

Michael explains to the judge how life is so complicated, people can never really be good enough.All of this is not only confronting to us in a moral sense but also seems to demand we fundamentally alter the way we consume goods.

And climate change is forcing us to reassess how we have lived on this planet for the last hundred years, because it’s clear that way of life isn’t sustainable.

Contemporary ethicist Peter Singer has argued that, given the current political climate, we would only be capable of radically altering our collective behaviour when there has been a massive disruption to our way of life.

If a supply chain is broken by a climate-change-induced disaster, there is no choice but to deal with the new reality. But we shouldn’t be waiting for a disaster to kick us into gear.

Making changes includes seeing ourselves as citizens not only of a community or a country, but also of the world.

As US philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues, many issues need international cooperation to address. Trade, environment, law and conflict require creative thinking and pragmatism, and we need a different focus in our education systems to bring these about.

Education needs to focus on developing the personhood of children, as well as their capability to engage as citizens (even if current political leaders disagree).

If you’re taking a certain subject at school or university, have you ever been asked: “But how will that get you a job?” If so, the questioner sees economic goals as the most important outcomes for education.

They’re not necessarily wrong, but it’s also clear that jobs are no longer the only (or most important) reason we learn.